Art and Politics against the Colonization of Time: An Interview with Dan S. Wang

Printer and writer, Dan S. Wang, talks about his projects that intersect art, politics, and labor—from teaching and public art with college students to anti-war and anti-prison activism, the Mess Hall, and the Compass Group—as collective experiments against individualizing economies of attention.

CW: Could you say a little about how you came to be involved in radical politics?

Dan: I can give you some personal history. I grew up in Michigan, in the industrial part. I was a kid in the 70s, seeing this economy change around me. I ended up going to high school at a place called Cranbrook, which was in the news lately because that’s where Mitt Romney went to school. It’s a private school in the wealthy suburbs of Detroit. So I was a prep school kid. It was there that I started to awaken to political thought that was outside of what I’d been exposed to or grown up with, and I started to understand Michigan history as having this rich, radical labor tradition, and also a rich counter-cultural history. A lot of the exposure happened through my self-directed explorations, but at the time we had many teachers who had come of age in the Sixties. For example, I had a teacher by the name of David Watson who taught a segment in my lit class. David is a renowned writer in certain anarchist circles. He’s written a few books that are out on Autonomedia, and a poet. He’s still there and now we’re friends. He was one of the core writers for The Fifth Estate, which was for many years a Detroit-based, radical publication (no longer Detroit-based), and which was also an important organ I discovered while at Cranbrook.

My first wilderness experiences also happened in those years, discovering all sorts of counter-cultural lit, developing tastes in music, all those revelations provided me an understanding of the whole counter-cultural tradition in the US. Being away from my family was important then, too. The separation allowed me to think independently of my parents’ values and expectations.

Then I went to college and my college experience was, on a class level, similar to Cranbrook. I went to school at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. It was the mid-80s and it was a very political time on campuses on a whole number of different fronts, in a fractured kind of way—this was the post-70s fractured Left: there was organizing around Central America, there was organizing around campus recycling (which didn’t exist at the time and was a radical idea), there was organizing around getting a sexual harassment policy in place (because that didn’t exist at the time, either), there was organizing around anti-apartheid divestment, all of these various compartmentalized issues. I came into campus activism at a time when the broad front of the 60s and 70s movements had really devolved into identity oriented issues or geographically specific kinds of things: there was a South Africa focus, an ancient forest preservation thing, etc. It was this interesting spectrum, or mosaic of issues and organizing that all had overlap, in terms of the people who were involved, but in terms of the analysis and language, there was a very fractured quality to it all (as compared to now).

That was when I really started to engage in a college campus setting. So, that’s a distinction to make. This was not a university. This was a college. It was an elite, private college. Small, homogenous, four years, carefully selected, a socially engineered community. But, we had great teachers, just like at Cranbrook. So, one of my teachers in Fall term of 1986, when I was eighteen years old, was Paul Wellstone. We read books by Milton Friedman and Charles Murray in his class. So, this whole idea, this David Horowitz bullshit, of leftists teaching a line, when it came to somebody like Paul Wellstone, is an utter lie. He was teaching across the ideological spectrum. We had great conversations in that class. Later that same year, I took a class from him that was sort of his trademark upper-level class called Social Movements and Protest Politics. It was a social movement history and series of guest testimonials about personal involvement in social movements. He had a lot of people come in to speak, who were either former students of his or through his vast network of Minnesota grassroots organizing campaigns. You’d have somebody from the P-9 Union in Austin, Minnesota, or somebody doing some family farm preservation stuff, or somebody who was a lobbyist at the State Capital for progressive causes. Over the years, a lot of students went out of that class and became organizers in some way or another. And that’s what I did.

That summer I worked for ACORN. It was a summer job, organizing in St. Paul and in Des Moines. It wasn’t very effective. I was nineteen, and trying to do this thing that I didn’t really understand. But, it put me in the trenches of going door-to-door in poor neighborhoods, and just trying to connect with people, and applying Alinsky principles and just seeing where it went. But, I was going back to school in the Fall, so it was essentially an educational experience for me, not a big investment in results. I didn’t leave any lasting effect in the places where I worked. But, it also gave me some insight into ACORN. And I followed ACORN stuff over the years, until it all went down through the sabotage by that asshole James O’Keefe from a few years ago.

After that, I had no schooling for a little bit. I went back to graduate school in art. The story there is that all along I’d been interested in art. I come from a family in which most of the children have some interest and talent for drawing. Art was one of my primary extracurriculars when I was a young person, and being exposed to somebody like David Watson helped, too. He came into our English class and did a three-week guest teaching spot, where he taught the novel Nadja by Andre Breton. I think it’s Breton’s only novel, a surrealist novel. It’s a drift kind of thing. It’s this half-imaginary figure of Nadja, this mysterious female figure, and the protagonist is just following this figure through the urban environment of Paris. This novel is one of the surrealist sources of what became psycho-geographical method and ideas of drift. Being exposed to the marriage of art and politics early on, that was my interest all throughout, while I was developing my skills as a draftsman and a printmaker in art classes. So, I returned to school for art, and I didn’t study art in college, so I had a thin portfolio and I wasn’t going to go to the elite art schools. I wanted to have a different experience. I knew that I had been educated in a very class-specific elite education. I wanted to go to a public institution.

I was fortunate to be accepted to do an MFA program at University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. It was interesting there, because the campus activism was really subdued. By that time, it’s the mid-90s and things are happening out in the world, but campuses are really quiet compared to the 80s. Furthermore, it was a big public urban university: a lot of commuter students, a lot of first-generation students, super diverse demographically. At the time, and even now, compared to other universities, there was a visible realization of its mission to serve the cross-section of Milwaukee. So, it wasn’t a campus with a lot of discontent or a clear antagonism between the administration and the students. And the political organizing happening at the time—say, things being done on a state and national level—wasn’t really happening on campus. While in graduate school the one consistent thing I did was clinic escorting.

There was an abortion clinic not that far from the university. Once a week, a group of us would meet there in the mornings and do the escorting of the patients from their cars, past the people that would harass them, into the clinic—a concrete defense of passage through public space. That’s what was going on: pitched battles over abortion. And that wasn’t really a campus issue.

Then, to bring it up-to-date, many years later, in 2007, I started to teach at Columbia College as an adjunct professor. That’s where I’ve been ever since. Columbia is an odd institution. It’s a private art school that has a progressive mission. But, at this point in time and over the last year, the mission is running into its limits, economically, and the administration is now in a bind with its priorities, whether it’s going to be the mission or it’s going to be the economics. There’s been a lot of tension on campus and there are different campus constituencies that are organizing. I can talk more about that later.

CW: Thanks for that background. Is there anything significant that you want to talk about between your grad school days and 2007?

Dan: That was really about trying to fashion a career as an artist and what that would mean. I left graduate school with decent skills, because that’s what I really went there for. But, what I had shelved in the meantime were all of my interests in politics. So, I had this backlog of concerns having to do with politics. And when I moved to Chicago, which is where I lived for about ten or eleven years, that’s when I re-engaged with political stuff, but through the lens and the position of having some sort of status as an artist.

CW: What sort of political stuff were you involved in?

Dan: One of the more interesting engagements was through a grassroots organization in the place where I lived in Chicago: a neighborhood organization called the Hyde Park Committee Against War and Racism—just a small group of between ten and thirty people who met twice a month. The group was founded the week after September 11th. I started going regularly by about the fall of 2002, when it was starting to become clear that the groundwork was being cleared for the invasion of Iraq.

Anti-war protest, Chicago – (pic via Dan’s website – includes more of his print work)

We organized neighborhood antiwar projects. In the group I met people with whom I still work today, even though the group itself is pretty much defunct. Because this was in Hyde Park a lot of these people had relationships with the University of Chicago or hovered around the university, or were intellectual and academic by nature. This small neighborhood group included Rebecca Zorach, who is an art historian and an activist who does all sorts of outside-of-the-university organizing. She recently wrote a great article on this art gallery called “Art and Soul,” which was a project of the Conservative Vice Lords in the late 60s in Chicago, a completely forgotten episode. And Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, who is well known in socialist circles. She writes for the International Socialist Review, and has been involved in ISO for a long time. She’s recently completed her dissertation, I think in African-American Studies, at Northwestern. And a couple named Matthias Regan and Amy Partridge, radical academicians. I still work with these people. It was out of that anti-war work that I found an important part of my present day community of activist intellectuals.

CW: With that community are there any other projects that you have developed? I think I saw on your blog that you helped found Mess Hall. Is that a project that came out of those collaborations?

Dan: Mess Hall had a different genesis. That came out of a Chicago art world logic. MH was brought together by artists who have a strong critique of the capitalist and conservative tendencies in the art world. The original people were all art identified first, and they were motivated because of that. But it happened around the same time, parallel to the neighborhood organizing I described above. The HPCAWR organizing was activism first, but those of us who had art experience would serve the Committee by doing art stuff: producing images and signs and things like that. Mess Hall was the same combination of art and politics but from inverted starting points, where we were all artists first but we wanted to bring in an organizing element, an activist element, a social engagement element into a cultural scene. Or to just have the politics be informed by a framework of art. It wasn’t like we had a cause or an issue and were organizing around. But of course it just so happened that most of the people involved were politically informed. Even if not activists, everybody had leanings, anarchist tendencies. We had a natural tendency towards an anarchistic organizational form, at least officially a non-hierarchical form. And then within that, you would deal with the inter-personal politics. For me at least it was very important to have these two things, HPCAWR and Mess Hall, running in parallel, in terms of where my energy was going at the time.

CW: Did you see yourself as kind of a bridge between those two worlds of neighborhood organizing and radical artists? Were there ever any kinds of generative collaborations across those worlds?

Dan: Yes. There was an interesting ecology in Chicago at the time, where artists who were interested in activism and political engagement found each other, and found ways to work with each other, against the urgencies of the post-9/11 world. That definitely happened. Things emerged out of that ecology, some of which remain interesting today. For example, the Tamms Year Ten project, which is a grassroots initiative aimed at shutting down the Tamms Supermax prison down at the southern tip of Illinois. The principal organizer of that group is an artist, named Laurie Jo Reynolds, who does video and media art. She’s art school trained, but her grasp of organizing goes way beyond that of your average political artist. She possesses an amazing understanding of how a grassroots organization might amass the power to bend legislation, and how to be heard and be visible, and how to get that position onto a state legislator’s agenda. Knowing that the only way for Tamms to be shut down is through it being zeroed out in a budget, and that the agitation is fine and is useful at times, but the real pathway toward shutting that prison down is going to be through lobbying, and the flexing of political power on that lever—to me, it is so heartening to count as comrades activist artists who know what it means to play hardball. This is a really interesting problem for radical artists, who in many ways by nature are very friendly to anarchist formations and working completely outside of official channels. But, because Laurie Jo is an artist, she has a really good understanding of how to bring art, image making, messaging, creative organization, into that cause. [Update: as of January 4, 2013, after years of struggles, the Tamms Supermax Prison was closed.]

Chicago rally to shut down the Tamms Supermax Prison (pic via Tamms Year Ten)

CW: I’ll pull our conversation back to the university. Since you started teaching at Columbia College in 2007, could you talk about what organizing you’ve been involved with there?

Dan: Well, I will say that I haven’t really been involved in the campus organizing at all. I’m a member of our union, Part-time Faculty At Columbia (PFAC), and it’s a strong union. Columbia is an unusual school in that 75% of their faculty are part-time. Because it’s a school of creative and performing arts, one of the ways they’ve built up their faculty is by inviting in lots and lots of people like myself, who are more or less happy to teach part-time to augment our independent careers as practicing artists. So even within the part-time faculty, there’s something of a split in terms of those who really depend on teaching for a living and then those who have other sources of income outside of their part-time teaching. It isn’t an open split, but it is a difference in terms of how invested people are in the fight. But, that’s what the union is for: they perform the fight for us. The union evens out the level of personal investment, and in the end we all benefit from it. For myself, because of my personal situation with the person I’m married to, I don’t have the same pressures as some of the people who really have to max out on teaching, and I’ve been able to pursue freelance sources of income. Nonetheless, I do benefit from what the union has bargained for us. For example, the union demanded that the school put its money where its mouth is in terms of the part-time faculty as professionals. The school markets itself as, ‘you come to Columbia and you’ll be taught by people who are really active in the field,’ and that includes all of these part-time teachers. The union said, ‘if that’s really true, if you value all of these professionals, these people with a status of having achieved highly in their field, you should help them continue to do that, you should offer research fellowships for the part-time faculty, not just the full-time faculty.’ I’ve benefited from that, because I’ve been awarded a couple of those grants. Most schools don’t do that. There are many concrete benefits that come from the union.

Most of my campus engagement, in terms of the political situation and activism happening on campus, has been through my students. With Occupy there were some Occupy Columbia chapters. In the spring, I had one student in my class who was one of the principal organizers of that. She was involved from the beginning with Occupy Chicago. We really wove into my assignments, which was a print media class, the work that she was doing for these groups. We had excellent discussions.

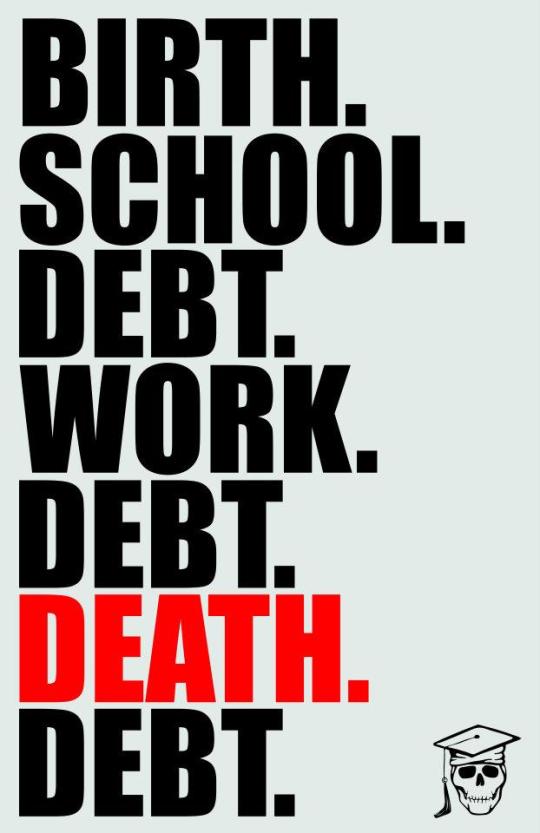

CW: Is she the student who made the poster on your blog of ‘Birth – School – Debt…’?

Dan: Yes. For example, that blog post sums up some of the ways that students engage on campus stuff, and I did my best to encourage them to assert themselves, in terms of putting their voices out there. We talked about how to do that, about the risks you take, and the questions you should be asking yourself in terms of: what is the reaction you’re looking for? How does this advance the struggle in a positive way? Bringing those questions is my responsibility as a teacher who has experience making stuff for movements.

My freelancing and independent activity includes being invited to places as a visiting artist. I get short-term involvements with other campuses, where I get to have a little taste of another school. For example, in 2012 and 2013 I made three visiting trips to Kalamazoo College in Kalamazoo, Michigan. I was invited there specifically because they had a campus controversy going on, having to do with a mural. The fact that this mural was over 50 years old; it was from 1949 or something, post-war period. The title of that mural is “The Bridge of Life,” by Phillip Evergood, a well-known painter of the day. It is a representation of the campus with dozens of figures in it, and just about all of them are white. The mural takes up a whole wall in the dining hall that is the school’s main campus social space. A group of students of color had approached the president, asking her to add an interpretive text, like a plaque or something, that would acknowledge that the campus no longer looks like this in terms of its social makeup. Some faculty thought that maybe we could use the controversy to really create a campus conversation, and not just do the easy thing of putting up an interpretive plaque. So they invited me to come help frame that conversation, to jump start it, and to talk about the issues having to do with representation in art, and how those reinforce or stand in contradiction to different sets of values, and different realities. So, that was an entirely different kind of thing, but is was also set against a campus environment.

CW: How did that go?

Dan: I thought it went pretty well. I was trying to advance the conversation beyond a complaint about not being represented in a picture, and to really look at the picture and see what it says about the world we are living in now. What I mean is, the mural has all these people in it, yes, but it is also a picture of the campus and town. There are some parts of the campus that are visible and recognizable.

Philip Evergood mural, The Bridge of Life, at Kalamazoo College – (via Dan’s post about the mural project)

There’s part of the composition showing people who are laying bricks, and they are building a structure that’s like a half-finished bridge, kind of in the mid-ground, this structure being built with workmen, and then in the background it’s fields, pastoral and with some campus buildings, and on the left side a depiction of factory work. My thing was, being from Michigan, look at what the people are doing in this picture. They’re building something, this architectural structure. Now, go outside, walk around Kalamazoo. Walk around any of these industrial cities in the southern third of Michigan, and do you see much being built? The structure that was being built at that time of the painting, in the 1940s, it’s probably crumbling now. That, to me, is as indicative of a great social transformation we’re undergoing, as much as the ethnic and racial makeup of the figures on campus.

My thing was like, ‘let’s talk about this picture in terms of world historical, economic transformation.’ It’s not just the social justice thing of including more and more groups into our democracy. That’s part of it, but that’s actually in some ways the small consolation of capitalist democracy. The bigger part, the part that really is shaping the material world that we’re all living in and dealing with, is the fact that three generations ago cities in Michigan were all about the construction of this world. And it says something about where people’s imaginations were, their ideals and sense of what was possible. Now, you go to Detroit, you go to where I’m from, Saginaw, you go to Flint, you go to these places, and everything’s falling apart, and what does that do to our imaginations? How does that open up our imaginations differently? This is what I was trying to bring into the conversation.

I feel that young people, particularly people who are interested in identity issues, often have uncritically inherited the reductive tendencies that my generation had played a big part in establishing in the 1980s. So, when I was telling you about the 80s, all of that campus activism and the way things were fractured, the way identity became really strong as a concern–it informed the whole sexual harassment thing, it informed demands for diversity requirements in academic subjects. Those are all real achievements. Students I see now, they’ve inherited that vocabulary but not necessarily in a good way. The first thing they go to, when they see this mural, is to complain that there are no black people, no brown people, no red people, and stop the analysis there, implying that it can be corrected by adding those people. I visited Kalamazoo College in the hopes of moving the conversation beyond that.

CW: So, you’re trying to destabilize the sort of liberal imaginary that values diversity and inclusion within the existing political-economic system?

Dan: Exactly. And I was trying to bring in the self-awareness that this is Kalamazoo College. It’s a place kind of like Carleton. It’s elite, wealthy. Kalamazoo is like all of these depressed Michigan towns that still have a lot of wealth in them, because there was so much wealth generated there in the past. There are wealthy families that fund the place, that sit on the boards. They have this amazing access to resources. I had a couple of small group meetings with students of color who come in through a recruitment program called the Posse program. They were from South Central LA and East LA; they were basically tourists in the Midwest. They don’t feel comfortable in Kalamazoo. It’s not their place.

I was trying to tell them: you need to get over that. Not in exchange for any up-by-the-bootstraps mentality, but rather to understand that institutions like Kalamazoo College really are clubs, and that they’d been admitted for life. That’s how the College looks at you. You’re going to carry that with you, that brand, for the rest of your life. You’ve been admitted. You’re in. And you need to treat it that way. You need to come out and say, this place is my place. I’ve been admitted here, just like everybody else has been admitted. And it’s going to be my place for the rest of my life. That’s when you can really establish yourself as a leader, with a leadership voice, rather than just as someone who comes to the party and ends up complaining. I was trying to encourage them to be more secure in the fact that when you’re admitted, it’s really difficult for you to be kicked out—no amount of microaggressions can take away your membership. You have to do something egregious, almost violent, to have your full membership erased. And because you belong wholly and permanently, you should demand more. That was my message. Demanding a corrective, based on, ‘oh, you need to populate this image, or you need to acknowledge the fact that it’s all white.’ That’s demanding the minimum, and that to me means that you still have a mentality of being marginal. Really, what you should be demanding is way more than that.

[To read more about Dan’s work on this mural project, see his blog post, “Murals on the Mind in Kalamazoo.”]

CW: This is great. I’ve always thought of universities’ branding as a negative thing to be fought against, but I haven’t really considered these possibilities of using the university’s own self-branding as a kind of tool for subverting the university’s more normalizing purposes. Empowering students to recognize how they’re being branded as members of that university or college and how they’re going to carry that brand with them the rest of their life, and to recognize that and to demand more: that’s awesome. Have you taken that approach at Columbia in Chicago at all? Or are their ways you’ve tried to get students to think about their own positions in Chicago and to relate that with the wider place in the city?

Dan: When I address the students on the topic of the College, a lot of it is about the cost of the College. And I’m constantly encouraging them to really get their money’s worth, and to use the faculty and resources as much as possible. I don’t think Columbia students have the same brand investment and active accumulation of value in the brand (of having a Columbia degree), not like there is with Carleton or Kalamazoo College, where students are cultivated as lifelong members of the club even before they graduate and the culture of the school is projected well into adulthood through giving. In general, people who study art and go to art schools don’t end up making a lot of money. So, there isn’t the same lifelong attachment. I don’t think there are any reunions at Columbia, as far as I know, for example. So, a lot of what I end up trying to communicate to my students is getting what you can out of the experience while you are there, and emphasizing a lot of the things they have already paid for—all of the speakers that come to school, the library, and things like that—to really use them.

Apart from that, in my Intro classes I don’t have a lot of room to talk about political stuff, other than just announcements or general, national things. In 2008, we would talk informally about the presidential elections. Current events leak into the classroom, but on an informal level. I can’t say until this spring, when I taught this political print media class, that I really had a class that specifically had political content as part of the syllabus. The intro classes that I’m responsible for are very skills-oriented, so there’s not a lot of conversation about messaging or content. I’ll always have one or two students in any class that are interested in political stuff, so it’ll be through them, but it’s not part of the syllabus. I’m speaking to different interests for every student.

On the balance, I have to say that the students now, especially at Columbia, they do searches on their faculty before they go to class, so they know what their faculty are into. And my students oftentimes are surprised that my classes are so apolitical. Maybe unpleasantly surprised. Maybe they’re expecting something different, something more preachy or with more overt posturing. And that’s just not relevant to what I’m supposed to be teaching.

CW: Do you feel part of the reason that you focus on teaching skills that you’re kind of respecting students in their economic investment in the classes, and that you’re trying to help them acquire skills to have a kind of art career to enable them to pay back their student debt and support themselves?

Dan: Well, I wouldn’t instrumentalize my motivation in that way. I guess my interest is more on an intellectual level. At a profound level, at a somewhat abstract level, you could say this is political. But what I teach is traditional print media, and why I like to be as convincing a teacher as I can in terms of relating those skills to them, is because those skills stand in opposition, in many respects, to modern life. So, for example, I teach woodcut, and woodcut is really slow, and there’s no way to rush it. It’s an analog process that forces your mind into a kind of different zone of reflection and meditation, focus and patience. It’s not only hands-on, materially concrete, and tactile, but in terms of the temporal dimension it’s very slow, especially compared to how these young people, who are really screen-oriented, have grown up. So, I start with that. And I start with black-and-white—because there’s nowhere to hide. There’s only a black element and a white element, and you have to just use that to make some sort of convincing image. There are all sorts of quirks. It’s mirror image. You’re printing off of a board. There are reversal image issues, there are positive-negative issues. It’s very confusing, and it really takes time to sort out in your mind, what’s going to be what, and to map it out. It takes a lot of discipline. The ones who really master it, who really get into it, I feel like they discover a new way of thinking—that they value because it’s not what they find served up in everyday media. I can only hope that there’s something valuable in that. People garden for the same reason a lot of times. They’re like, ‘oh, it’s not even about the food or the flowers, it’s just about the seasonal thing and the time.’

CW: Thinking about the temporality of it, would you say it’s not only the pace of time that’s different but also the quality of the time? I’m thinking of the distinction between lived time vs. clock time. It seems like a kind of time that you have more control over, rather than being inserted into the time of capitalist machinery.

Dan: Yeah. When we do the black-and-white woodcut, there’s a short essay that I like to read as a class with it, which is called “Art and Labor.” I am interested in introducing into the conversation the idea that capitalism is really about the colonization of time, the regimentation of time, and the production of value through the control of time. And how art-making both reinforces that and, yet, we can find ways de-stabilize that construct, or at least reveal it for what it is. But, you know, I don’t have time to explain Marxism or to explain the division of labor or the industrial revolution—all of these things that would make real our current arrangements and where they came from. But, yeah, part of that conversation is at least touching on that idea, that there is a connection between labor, time, and value, and that has something to do with why people don’t do woodcut anymore—except artists.

CW: I want to take your class! Stepping back a bit from pedagogy and the university, thinking about radical movements more broadly, and thinking about the work, teaching, and activism that you do, what do you feel are some big obstacles or limiting conditions that you and your collaborators face? What prevents you from doing more radical stuff or making the radical pedagogy and activism that you do more effective and expansive?

Dan: That’s a great question, and there’s one particular thing that I’ve been thinking about a lot over the last few years. That is, how all of us who are artists and who have some sort of status as artists and who are also political activists and have radical values, we operate in an economy of attention. Resources are allocated in a system that is biased toward individual authorship. Even if it’s not individual authorship, it’s still identifiable authorship. So, when myself and some of the people that you’ve met (like Claire, Brian, Rosalinda, Sarah) people that I work with, sometimes we use a name called Compass, when we do something where authorship is required, like in a group show or something like that. Other times we don’t use authorship at all. Sometimes we use this name Compass as a pool for opportunity and recognition. So, maybe one of us will get an invitation to do something, and we’ll just bring it to the group and we’ll be like, ‘well, I don’t really want to do this alone. It’s with a prestigious institution. Does anyone need to do it for their career, so that when they need to, they can say here’s my individual CV, and here’s a project that I did with this prestigious museum?’

So, it’s kind of an experiment in that way of pooling opportunity and sharing achievement, and working against the logic that holds back all of our projects, because it’s exactly that. When resources are doled out on that basis, what it does—and this goes back to that temporality thing—it regiments our time, because then it’s like, ‘I commit to that opportunity, which means I have that deadline, I have that month booked up.’ And this becomes a real problem when the group of us get together and we’re like, ‘here’s the group project we want to do.’ (For example, we have a book coming out, Deep Routes: The Midwest in All Directions, in the next few weeks that we assembled together.) And in that process of assembling, it’s like, ‘who can do this?’ And everybody goes through their calendar and they’re all booked individually. Basically, it takes time out of the common pool and puts it into individualized calendars: a kind of privatized temporal experience of labor, where we can’t coordinate our labor anymore. This is a very concrete limit that keeps us from acting as a collective force, a collective intelligence and presence.

Most artists, the vast majority of artists, are just completely unconscious of this. It’s just a given that this is how it has to be. But the more that we have this collective commitment to working together and to build on things we’ve done in the past, the more obvious it’s becoming a problem.

CW: I feel that there’s definitely a similar sort of problem in academia.

Dan: Then, I’ll say the thing about academia is, yeah, I feel that academia has its own logics of what people have to do to get their jobs, to get their promotions, to get their security. I can’t speak first-hand as much about it, but I do get the feeling that it keeps certain kinds of research from being done. Because you have to do a certain kind of research that has a quality of authorship and a timeliness that just precludes all sorts of other collaborative, experimental, exploratory, collective kinds of research that are begging to be done. Researchers may understand it intellectually, but the structure of the university, and it how rewards achievement, just won’t abide those less individualistic ways of working and thinking.

CW: It sounds like you and the folks in the Compass group have talked about this explicitly. Obviously, you have well-developed thoughts on this. And you said that most artists are pretty unconscious about this problem. I wonder if you and the Compass group have thought of ways to popularize this kind of critique of how our time gets individualized.

Dan: I think it’s just starting. That’s something that I’d like to do some writing on. The conversations have been informal, and they have come out of the fact that we perceived the limits.

CW: This is a conversation that, in the radical academic organizing world, has only begun to be theorized a bit. It’s hard to convey it in non-jargony terms. I feel a big challenge for us is to translate our theoretical ideas into more easily popularizable forms. Maybe one problem, at least for academics especially, is that we get to caught up in a kind of linguistic mode of communication and neglect, or just don’t have the skills, for visual forms of communication. That’s where I feel like some artist and academic collaborations, such as those that you are involved in, could be powerful popularizing these ideas.

Dan: I do think that collaborations with academics, for artists, can be a real service to academics. My impression is that academics are a lot more constrained, that disciplinary structures crowd out the space in social science to be really experimental. And to have artists, who have a recognized status as an artist be a collaborator, I think is something we have to do more of.

CW: Do you have any last thoughts?

Dan: Yeah, my last thought is that I live in Madison, so I do hover around this university: a flagship state university, world-class research university, and I do have to say it is something worth defending, because it is a tremendous resource that belongs to the public, that was built by big public investments from previous generations. The piecemeal incursion of privatizations of all sorts is really alarming. It is a public resource in a way that the University of Chicago, or Carleton College, is not. You don’t have to be in the club to get something out of this university, or rather, all the people of Wisconsin are supposedly in the club— because of the whole ‘Wisconsin idea’ as a founding concept. So, that’s why we’ve got to defend it, even as we criticize it. That’s an Edward Said position. You’re a partisan, but you’re always critical of your own side; you always demand that it be better. You’ve gotta fight the external enemy and the internal battles at the same time. And that’s a difficult thing to do.

***

Dan S. Wang is a printer, writer, and blogger living in Madison, Wisconsin and teaching at Columbia College in Chicago. This interview was conducted on 5/26/12.

Reblogged this on Free UniversE-ity.

I really like what you guys are up too. This sort of clever work and reporting!

Keep up the very good works guys I’ve added you guys to my personal blogroll.