A Brief History of (CUNY) Time: Recent Radical University Organizing in NYC – Interview with Matthew Evsky (Part 1)

Summary:

Drawing on first-hand experience, Matthew Evsky* shares a recent history of student and labor organizing at and around the City University of New York (CUNY), including the Adjunct Project, Campus Equity Week, the CUNY Time Zine, Occupy CUNY, and the Free University of NYC. He delves into the complex relationships between students, contingent faculty, the broader faculty union, and the confusing processes of university exploitation. The emergence of Occupy CUNY burst into a week of action with a student sit-in that was violently repressed by campus security. Although seeing undergraduate organizing as the driving force behind a revival of campus activism, Occupy CUNY connected radicals with each other and built supportive direct relationships across divisions of workers and students. Emerging from a working group on radical pedagogy, the Free University of NYC has enabled people to transform classrooms into spaces of radicalization.

The Adjunct Project and Contingent Labor Organizing at CUNY

CW: Could you say a little about how you’ve come to be involved in radical organizing, particularly in relation to universities?

Matthew: For me, I feel like that starts in graduate school. I don’t remember exactly a transformative moment, but I do remember arriving at CUNY [City University of New York] and seeing people tabling. There were folks organizing under the name Adjunct Project. While I don’t remember exactly when I became interested and started working with them, I do remember the moment when I had no clue what they were doing or what the word ‘adjunct’ meant. Basically, I recall being in school and not having any consciousness of the university re-structuring or of the university labor market transformations, of corporatization. Through personal connections, I was then beginning to work on projects with the Adjunct Project, and beginning to learn an analysis of CUNY that the Adjunct Project had already been working on, and to help contribute to that analysis and to teach it to other people—the neoliberalization of CUNY, or the narrative of CUNY as a public institution that is privatizing through fees and transforming its labor relationships and so forth.

I didn’t do education-specific organizing in undergraduate. It wasn’t necessarily something that I was aware of. I was in the UC system. There were people organizing hoping to reinstate affirmative action. That was one of the bigger organizing goals of the radicals who were education-centered when I was in the UC system in the late 90s to the early 2000s. I wasn’t specifically a part of that. I didn’t have a good understanding of that system or what it was about. I knew that tuition was increasing, but I didn’t know it as a strategy from the top to transform the relationships of education and work and all these things.

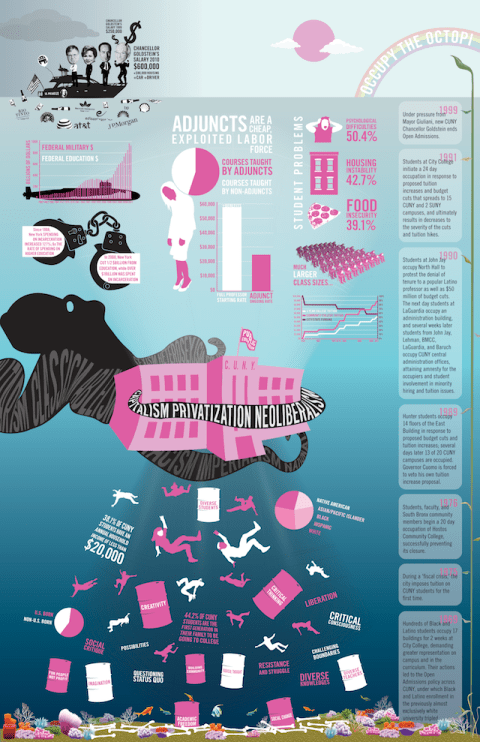

So, it was definitely my first and second year of grad school that led to working with the Adjunct Project. One of the main things we worked on was something called Campus Equity Week. We put together a series of agitational materials that were for teaching undergraduates about the neoliberalization of CUNY. Among those were a poster that allegorically described CUNY as a factory with adjuncts sort of as part of the moving parts and students as also part of the moving parts. The students, after going through the classroom, fall into a PLINKO board, which represents their general precariousness: as they fall through the board, only one or two of the students receive actual gains from the credential, and the rest of the students receive precarious underpaid work. Also, the poster had various stats such as budget trends and average salaries throughout the CUNY administrative and faculty hierarchies.

In addition to the poster, there was a powerpoint and other materials. We planned to find professors and adjuncts who would teach this material in the classroom and/or we would teach it in their classrooms if they didn’t feel comfortable with it or didn’t want to take the time to prepare. We printed the posters, and we tried to get it out there, to train people to do it. I did it in my classroom and in another person’s classroom. There was a bunch of other people who were trained and did it in their classrooms as well as others.

I didn’t leave that process thinking anything palpable had shifted. We were excited by the end products, and we were excited when people we talked to were into it, not just in CUNY but also when we met people at conferences and other places. We also heard practical criticisms of the poster, the main one being that it’s confusing, that there’s too much going on in the image to be useful.

Before the Equity Week poster, the big thing that we worked on was the CUNY Time Zine. There were people interested in doing a DisOrientation Guide. I don’t know the history of DisOrientation Guides, but it seems that in the mid-2000s there was a bit of a moment for them. A few different schools across the country had produced them [e.g., read an interview on the UNC DisOrientation Guides here]. Some of them were quite large and quite compelling—just the notion that, ‘here’s a guide to your university,’ usually involving workplace issues, investment issues, and also, generally acclimating students to where are the radical spaces, what are the safe spaces, what are the things to avoid—an orientation guide for people who would want to know that their university is a corporatizing behemoth. So, we had a couple people coming into the grad center who were excited about doing a DisOrientation Guide, and we met a few times in order to make one. But, we ran into the problem of: would this be a DisOrientation Guide particular to the CUNY Grad Center, and if so would that be useful? We also thought that this could be a DisOrientation Guide for one of the campuses, but we weren’t particularly attached to any of the campuses. That killed a bit of the momentum for it, so we ended up doing a zine called CUNY Time, which included things like an article on tuition, privatization, and corporatization. It also included a power map, which was essentially an illustration that outlined some of the hierarchical elements of CUNY’s power structure: how many people are on the board of trustees, and where do they come from, how many people are on the university and student senates, etc. That was more of a visual thing, and we wanted people to think of how they would re-structure the university if they had to move things around. There were also some humorous zine-type elements to it: images and quotes here and there. We ended up doing an updated version of the first one, with some new material, and then a second one. So, there are three different CUNYTimes out there.

Download the CUNY Time Zines here:

- Issue 1: (web viewable) or (printable booklet)

- Issue 2: (web viewable) or (printable booklet)

After the CUNYTime zine, we did Campus Equity Week [check out this flier from the Fall 2009 Campus Equity Week]. Then, there was a period where the Adjunct Project really struggled. The relationship of the Adjunct Project to other more hierarchically organized groups was creating problems. The Adjunct Project at that time was organized as a consensus-based, horizontal group. However, it did have funding from the Doctoral Students Council (DSC), basically as their labor wing. Although the DSC didn’t really meddle in the Adjunct Project’s affairs, other than choosing the paid people: there were co-coordinators. The group had a couple marginally paid people that operated using consensus and in a horizontal fashion, mostly. The other organized group that I’m talking about is, specifically, CUNY Contingents Unite, which is a group of contingent organizers that came out of a campaign to vote ‘no’ on one of the union-negotiated contracts. There was a union contract, the last contract, when it came up to be voted on by the membership, it was apparent that the union leadership had, for the most part, sold out the contingent workers. So, a group of already-radicalized contingents basically put together a ‘vote no’ campaign, and that campaign turned into CUNY Contingents Unite.

CW: Could you give a quick background on the relationship between contingent faculty and the broader union?

Matthew: For sure. Contingent faculty at CUNY, which can include graduate students who have fellowships that require that they teach and who have assignments at different campuses, professionals who are adjuncts—such as lawyers who teach at the law school—and also quite a few people who have masters or PhDs and simply are full-time part-time employees, i.e., their contracts are for one semester, usually, and they are paid on a contingent pay scale. All of those people are represented in our union, the Professional Staff Congress (PSC). So, everyone who is a part-time worker as a teaching instructor is already a member of our union. However, the way the union works is very confusing, and has been very confusing with how to actually organize contingents. So, one of the things that we did was to try to map out this process. Basically, the bargaining unit of the PSC is somewhere in the range of 25,000 people. Of the bargaining unit, maybe only 15,000 or so are members of the union, meaning that they’ve signed their union card. But, all 25,000 are represented in the contract. Then, the make-up of the bargaining unit: the number of adjuncts and contingents in the bargaining unit, I think it’s something like 60/40 or 55/45. It’s close to even of full-timers vs. contingents, swayed a little more toward contingents. But a significant majority of members are full-timers.

So, the situation in the PSC is that you have a large group of people who are not becoming members, but of that group of people, it’s overwhelmingly contingents. Why? Obviously all the reasons we can imagine: you just arrived on a campus, you don’t have an office, you don’t have any support, you don’t know if you will be a worker there later on. I haven’t been on every campus, but from my experience at Queens, there is not a lot of general grassroots-type organizing by the PSC that would put you in contact with other organizers. So, you have this huge group that is well-represented in the bargaining unit, but under-represented in the membership, and that process gets starker the higher up in the ranks that you go in the PSC. So, in the PSC, being the type of union that it is, members essentially don’t do very much other than vote for elections, which can sometimes be relevant, like when the current leadership beat a more conservative leadership. But other times the elections are really meaningless due to the union structure. Members do not actually have voting ability on things like policy or bargaining priorities. Those things are decided upon by the executive assembly and/or the delegate assembly, and both of these bodies are like the membership as a whole, overwhelmingly made up of full-timers over contingents. The delegate assembly meets, votes on stuff, and then there’s an executive committee where all the power actually resides. There are a couple contingents on the executive committee, but mostly not. Each campus has a PSC chapter, and those are in a sense the shops within the union. They each have an executive committee, and they do things, but the chapters really struggle to have contingent participants, again for all the same reasons.

CUNY Contingents Unite is basically a contingent, non-affiliated group of members within the union. They’re a rank-and-file group that was contingent-based. They’re for the most part pretty cool, since they focus on adjunct and contingent needs and really target how the union leadership hasn’t sufficiently addressed the situation of contingent workers within the bargaining unit, and precarious work in the university as a whole. One or two of the lead organizers in their group come out of a very hierarchical internationalist-style of organizing, and that’s the color of that group. So, to get to the relationship between those groups and what I was saying with the Adjunct Project: we were struggling with people having different impressions of how to organize the Adjunct Project. Some folks, not overtly so but in the way that they were acting, were not really wanting it to be a consensus-based organization and other people were wanting it to be a consensus-based organization. And, that was making it difficult in Adjunct Project meetings to accomplish stuff. Essentially, the environment was not cooperative, for a certain period.

The Adjunct Project essentially became a solidarity organization for Occupy CUNY, which emerged in Fall 2011 with the Occupy movement.

A section of the “Occupy the Octopi” poster

Occupy CUNY

CW: What does the Adjunct Project look like now in relation to Occupy CUNY?

Matthew: As far as I can tell, the Adjunct Project identified that it was not going to be a vehicle for CUNY organizing in that moment. But, the three paid staff members, along with other satellite people, recognized that they would continue to do what they had been doing, but that the Adjunct Project wasn’t going to be the vehicle as the name ‘Adjunct Project.’ The whole Occupy CUNY started with just a call for a general assembly at the Graduate Center, so when people started attending those assemblies, then with the Adjunct Project, because some of those people were paid and had a budget, they made their resources and budget available to the general assembly. And, they tried to orient the general assembly toward adjunct issues, in addition to other things, but not in a bad way. As individual organizers who were concerned about adjunct issues, they were bringing that stuff to the table, but not in an intense and stubborn way.

CW: How is Occupy CUNY going? How have you been involved?

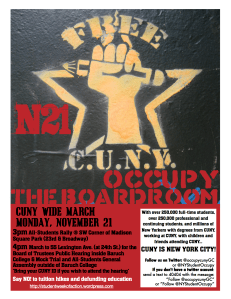

Matthew: Yeah, I’ve been involved in Occupy CUNY. There’s a lot to say about it. It grew up really fast; super quickly there were general assemblies with 100 people, essentially using the tools Occupy Wall Street was using: the consensus-based hand signals, holding assemblies, holding a week of action in November. During that week, there was a march one day. The night before, there was a faculty speak-out. These were the first movements of Occupy CUNY and the general assembly, and they were very potent. The faculty speak-out was really well attended, and also quite an inspirational evening, and sort of showcased the willingness and ability, at least partially, of faculty to participate and to self-organize somewhat.

The march the next day was preceded by a speak-out in the atrium of the Graduate Center, which was incredibly potent: staff, students, grad students, some faculty, some low-level administration—people speaking out. I can recall strongly the feeling of that speak-out; I’m kinda tingling a bit just now thinking of it. People were crying. People were speaking from their heart. Some students were like, ‘I spend most of my time in this building being totally fearful, fearful of talking to professors, fearful of talking to staff, fearful of where I’m going to be in a couple years, fearful of not having any job prospects or even just funding next year.’ And then a staff member would speak out later and be like, ‘I really hope people aren’t fearful of coming into my office.’ It was a kind of dynamic where people were keeping it real. The differences of privilege and access at CUNY are huge and complicated, but I think that speak-out really peeled back the layer of the facade where everything appears to be ‘all good’—to expose how cancerous everything is at CUNY. Then there was a march, which was also great.

The following Monday after that week of action was a public meeting of the Board of Trustees. I think that Friday was when the students at UC Davis were pepper-sprayed, and then that Monday was when CUNY campus security violently charged a bunch of students in the Baruch atrium, basically blocking people from attending a public meeting, and then, when they sat down and were going to hold a general assembly, the guards were ordered to charge those students, and were pushing them with batons, trying to push them out a revolving door. All of this stuff is available on YouTube (See this video: “Occupy Everything at Baruch” – and other videos linked here along with a “Statement Condemning Police Violence at CUNY Board of Trustees Hearing”). That really just followed up in the heels of UC Davis. Fifteen students were arrested: ten of them were detained for the evening and released, and five of them were sent to central booking.

Campus security repressing student protesters at Baruch College – November 11, 2011 – (pic via John Zhang, “What Really Happened at Baruch”)

That was a moment where the follow-up general assemblies were huge because people were like, ‘what just happened?’ On top of it, the November 21st Board of Trustees meeting was really just a public input meeting in order to vote on the tuition increases the following Monday. So, November 21st was just a sham forum, and the 28th was the real vote. So, people were like, ‘now we need to mobilize for the 28th.’ On top of that, Occupy CUNY had to grow up really quickly. There were no members of the National Lawyers Guild present initially on the 21st. There was no support group that was prepared to deal with 15 students arrested. There was no understanding of legal issues. I mean, we had been doing that stuff a little bit, but November 21st showed very quickly that Occupy CUNY had to mature into a group that was able to plan actions to the fullest level, including jail support, including tapping into other sources of solidarity, such as faculty and National Lawyers Guild, etc. There was an action on the 28th, which resulted in two arrests. Occupy CUNY kind of developed from there. They’ve done tons of things since then.

CW: Do you feel that Occupy CUNY has re-invigorated radical organizing on the campuses? Has it been symbiotic with other kinds of organizing, like labor organizing with adjuncts?

Matthew: I don’t think that Occupy CUNY at the Graduate Center has necessarily re-invigorated radicalism at CUNY. I think that undergraduates at CUNY have done that in the groups that they’re a part of, specifically the Brooklyn College Student Union and Students United for a Free CUNY, and the work of New York State based groups, such as New York Students Rising. So, I would say that the undergraduates are reviving radicalism at CUNY. With Occupy CUNY at the Graduate Center, I think it did a really good job of bringing together all the various radical people. The Adjunct Project wasn’t particularly vital, but it had a group of maybe 10 or 15 people that were in its satellite world. Meanwhile, a whole bunch of new people arrive at CUNY every year who are pretty seasoned organizers or already radical. Between sociology, anthropology, geography, environmental psychology, English, as well as theater and a couple other places, you have another dozen to twenty people who are amazing and who are arriving every year. I don’t think the Adjunct Project was doing a good job of tapping into those people, whereas Occupy CUNY did, just because of the vibe. So, very quickly, people like myself who had been there for several years were organizing with people who were there in their first semester, such as people in theater who I normally don’t have any cross-over with and who were working on community-related projects. There was a generally positive speed-up of getting people on the same page—not as if everybody agreed on everything, but people were activated and in the same place, along with some professors.

CW: Do you feel that Occupy CUNY has also been effective for connecting people vertically across divisions of levels of education? And also across different levels of the workplace, connecting undergrads, grad students, staff—for organizing across those divisions?

Matthew: Initially, some students in Students United for a Free CUNY were pretty upset at the graduate student organizers. Being a grad student at CUNY is a privileged place: the demographics of the Grad Center don’t match the demographics of CUNY, and the demographics of CUNY don’t match those of a high school classroom. Definitely, CUNY’s own hierarchies represent real problems. But, a positive quality of the Grad Center is that, as far as I understood it, people at the Grad Center were bummed about being characterized as the privileged folks of CUNY and that those antagonisms were there, but people were particularly stubborn about not playing out those roles. So, there were a lot of people at the Grad Center who were building direct relationships and who were basically willing to work with undergrads in the context of, for example, if they were organizing an action and they needed resources, then not being overbearing and paternalistic. The fruits of that stuff came out pretty nicely on May 2nd, when two students were arrested at Brooklyn College and grad students at CUNY were extremely supportive without being overbearing and paternalistic, through jail support and other forms of support. I’ve also heard that Students United for a Free CUNY is less upset with the grad students, and that those relationships are now more solid.

Even years before Occupy CUNY emerged, grad students of the Grad Center were working with undergrads at Hunter, working with the Hunter Student Union, and that was around the time when New York City schools had seen a couple occupations, at the New School and at NYU, and there was organizing around whether or not there would or should be one at the CUNY schools. I had the sense then that there were tensions in the group between the folks who wanted to work in a consensus model, and this seemed to be the core of radical women of color, and a few male students who were maybe connected with internationalist, hierarchical organizing. My sense was that these tensions were making organizing difficult for the group. So, there was a time when Grad Center organizers were attending their meetings in support, but not trying to run the show or determine any outcomes. The way that I think about it is: consensus-based organizing has been the norm for me during the time I have been at the Grad Center. There’s always internationalist clubs at the Grad Center and of course CUNY’s long history of student groups includes a lot of different organizational styles, but for me coming in in the mid-2000s the center of radical activity has been consensus-based. Hunter Student Union was also a consensus-based organization. They had come out of the CUNY Social Forum, which was generally a horizontal project in the vein of the World Social Forum and the US Social Forum and such. So we worked with them in that fashion, especially when their group was being somewhat overrun by hierarchical folks. Mainly we would go to their meetings and not talk a lot but have a visible presence and talk when it was appropriate to talk, but being supportive of consensus-based work and of women-of-color leadership. That group, Hunter Student Union, doesn’t really exist anymore, but it’s an example of organizing across graduate-undergraduate lines.

I would say that Occupy CUNY at the moment has somewhat tapped into faculty and there are some faculty who are self-organizing, but Occupy CUNY has for the most part not been about adjuncts and contingents. It has not been a labor struggle around contingent and precarious work. It is but it isn’t. It is in the sense that that’s central to how the university is working, and Occupy CUNY is about a different kind of university. But, it’s not about contingent workers. Personally, I think it could be more. I think it’s a challenge, because it really requires building connections that are about the different groups of people at CUNY. The savviest undergraduates have an understanding of precarious work at CUNY, but most undergraduates don’t. For undergraduates, it’s not at the top of their list, rightfully so. But, I don’t see that there are groups that are about adjunct issues and other groups about undergraduate issues and they are forming compromises. It’s more like the undergraduate groups are about the tuition hikes, creating a free university—meaning a university that has no tuition—and other debt-related student issues. And, the graduate students are kind of Occupy organizers who are basically agitating against the CUNY admin.

This is maybe the biggest issue with Occupy CUNY at the Graduate Center: it doesn’t really, for the most part, have an identity, although it does a lot of cool stuff.

CW: Do you find that Occupy CUNY is lacking a shared common critique of what they see is wrong with the university, and also lacking a common strategy and vision of what they want to do?

Matthew: Right now, undergrad students are the ones that know their situation. But, grad students and other Occupy organizers are certainly the source of the analysis of the university. Even going back to Campus Equity Week and that other work, the students who become radicalized in many ways are radicalized by graduate student instructors who take the time to break down the situation. We had an open visioning general assembly in the springtime [of 2012]. A couple young people came who were undergrads at Hunter, and they essentially said, ‘yeah, we see the teach-ins and we kind of know what’s going on, but the real reason why we’re here right now is because our graduate student instructor took the time to break it down to us about how the situation is going, and did it in a personal way.’ Essentially, I’m saying faculty do have a role to play in taking the time to showcase to the students what is going on with their university, because it’s not out there. There’s no other way to get it. You can get it in a teach-in, but a strong understanding of what’s going on has to come from a stronger connection.

CW: Do you mean in their classes?

Matthew: Yeah, in the classroom, and over time—as something that takes time to develop and with relationships that require trust, which you can do in a short amount of time but for the most part doesn’t happen. In a sense, Occupy CUNY is a source of graduate student radicalism, and that has a place because it feeds into undergrad student radicalism in a specific kind of way, but more in the sense of analyzing and talking about the re-structuring of CUNY as well as the radical history of CUNY. At a certain point, I assume that that kind of analysis will just be reproduced within the student groups. So, like, the Brooklyn College Student Union, they know their shit, so they’ll just be teaching themselves. I do feel that in the late 2000s, as far as I’m aware, at CUNY there weren’t a ton of undergraduate groups that were analyzing the re-structuring and talking about adjunct issues, privatization, and tuition fees. That was coming out of the Graduate Center.

CW: Has there been a kind of collective, systematic effort on the part of radical grad students to help each other gain the skills and knowledge to do that kind of teaching about the radical history and analysis of CUNY in their classes? You mentioned that earlier with the Adjunct Project there were some trainings. Has that continued up to now and in Occupy CUNY?

Matthew: It hasn’t been going on formally, but only informally. Part of it is because, in the aftermath of Campus Equity Week, there weren’t any negative effects of it, but it didn’t feel like we gained traction. I don’t think people necessarily thought that it was a failure, but we didn’t keep on doing that. Campus Equity Week had been going on every other year, but we didn’t follow up with it. Now, there’s been talk about resurrecting that kind of stuff, ‘each one teach one’ or however you want to characterize it. The grad students are entering the classrooms all the time, so we need to teach one another about CUNY, so then we can, as grad students, teach our students about CUNY. These discussions have gone on for quite a long time, but the kinds of direct training and creation of material that I described with Campus Equity Week, that has not gone on.

“Occupy the Octopi” – via OccuPrint – Click here for larger, 11X17 pdf

There was another poster created in the Fall of 2011 about CUNY, which represented educational capitalism as an octopus. That poster was integral to creating Occupy CUNY. There was a teach-in using that poster in Washington Square Park, in the early fall, after Occupy Wall Street had started, but before the general assemblies had gotten really big. That teach-in was really well attended. I was at that teach-in but dealing with another issue. There were all kinds of people at that teach-in, from undergraduates to faculty, but mostly graduate students. As far as I know, that poster was never used in classrooms, but it remained an important tool that people learned about CUNY through. It just never became a systematic project of Occupy CUNY to take that into the classrooms. It was really just happening informally by the people who were in Occupy CUNY and were teaching.

I would say the bigger thing that came up was the Free University on May 1st, and that being a moment to take a critique of the way CUNY is going into public space, and into individual classrooms, but by people bringing those classrooms into the Free University on May 1st, which was in Madison Square Park. That looked a lot different from Campus Equity Week, but in many ways operated in a similar way, because there were people in the park who were teaching about CUNY, as well as other things.

One of the things that came out of the Occupy CUNY visioning session that I mentioned was the creation of a working group on radical pedagogy. It’s kind of interesting the way things start and the way they end up. There wasn’t just a single vision, but one of the visions for the radical pedagogy working group was that it would begin to use radical methods to train radical grad students, from the get-go at the Grad Center. They would aim to orient people that, ‘you’re going to be in the classroom; we should have methods that would, not just radicalize students, but teach students what’s going on with the political economy of the university.’ The first main thing that that working group did was that they became the Free University working group. Rather than institute some kind of long-term teacher training kind of notion of radical pedagogy, they did the Free University, and that was incredibly popular and successful. So, at the moment, that’s where that energy is.

*******

*Matthew Evsky is the pseudonym of a graduate student and contingent faculty member at the CUNY Graduate Center. This interview took place on June 11, 2012.

2 comments